|

BY TIM LAYDEN

© Sports Illustrated

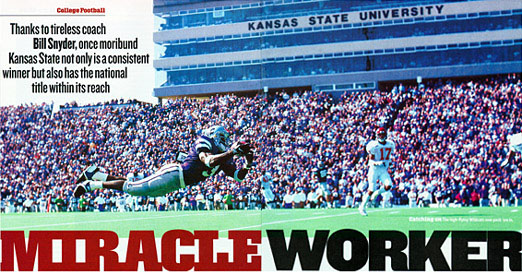

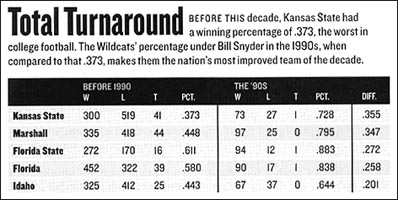

MOTHER AND son lived alone in a tiny three-room apartment at Fifth and Robidoux in the northwest Missouri city of St. Joseph. They had moved there from Salina, Kans., in 1945, after Marionetta Snyder divorced her husband, Tom, a traveling salesman. The son, Bill, was six years old at the time of the move. For the next 12 years he slept on a Murphy bed in the living room next to his mother, who slept on a rollaway cot. Bill learned to swim at the YMCA pool six blocks away, and he played five sports at Lafayette High. His mother worked tirelessly. She would leave the apartment before Bill awakened and walk to the Townsend and Wall department store, where she was a sales clerk and buyer. Often she wouldn't return until after Bill went to sleep at night. She never owned a car, never even got a driver's license. She just worked. "We didn't have much, but she provided me with all that she could. She literally gave up her life for me," says Bill. Marionetta died in 1996 at age 78. "She taught me that what the Lord gives you is time," he says, "and 24 hours a day is all you get." This workday ends at midnight, when Bill Snyder, 59, walks down the narrow carpeted hallway from his office into the foyer of the Vanier Football Complex at Kansas State, where he has been coach for 10 seasons. His only concession to the lateness of the hour is a slight loosening of his yellow necktie, which complements his gray wool suit. He pushes open a glass door and walks into the cool prairie night, pausing to lock the building because he's the last to leave. His dark green Cadillac sits at the curb. "You could drive by the complex after leaving a party at 2 o'clock in the morning, and his car would be there," says Kansas City Chiefs wideout Kevin Lockett, who played for Snyder from 1993 to '96. Senior tour golfer Jim Colbert, a Kansas State graduate and one of Snyder's best friends, often pulls out his cell phone late at night and dials Snyder's office. "Do you know what time it is?" Colbert's wife, Marcia, will say incredulously as Jim punches out the number. "Don't worry, I'm calling Coach," Colbert will say. "I know he's still there." As Snyder pulls out of the parking lot, his headlights briefly illuminate the expanse of Wagner Field, part of a 42,000-seat stadium (soon to grow to 50,000, plus 31 luxury suites) that once was home to the pits of Division I-A football. (In 1989 this magazine proclaimed Kansas State, with its horrific play before empty bleachers, the worst program in the country.) Now KSU Stadium houses a powerhouse, the most improved team in the '90s (chart, page 62). Snyder's Wildcats are 8-0 and ranked No. 4 in the nation after last Saturday's 54-6 victory over Kansas. K-State is a deep, veteran squad that mixes hellacious defense with a balanced offense. It has several computer-weighty games remaining -- on Nov. 14 against Nebraska, which it hasn't beaten in 30 years, against Missouri (Nov. 21) and, possibly, the Big 12 championship game (Dec. 5) -- and thus could finish first or second in the Bowl Championship Series rankings, which would mean a place in the Fiesta Bowl on Jan. 4, and a shot at the national title.

The mere confluence of these phrases -- Kansas State and national title -- is staggering. Barry Switzer, whose last three Oklahoma teams (1986 to '88) hung 185 points on the Wildcats, considered the effects of national college football parity and still concluded that Snyder's work at K-State broke new ground. "Bill Snyder isn't the coach of the year, and he isn't the coach of the decade," says Switzer. "He's the coach of the century."

Anybody else would eat. During the season Snyder eats once a day, when he gets home, usually well after midnight. He doesn't eat other meals because, he says, he discovered three decades ago that "you can get a lot done during the lunch hour, and shortly after that I realized that if it works during lunch, it works during dinner." Anybody else would sleep. Snyder snags four or five hours a night before driving back to the office. Anybody else would find a way to put down the VCR clicker while exercising. Snyder works out on a stair machine in his office while studying tape. Anybody else would let it slide when butter is served at a team meal instead of the requested margarine. Not Snyder. Anybody else would lighten up. Snyder doesn't. He insists that he has interests outside of football -- boating, swimming, reading -- "but I just can't pursue any of them at this point in my life." Even in rare moments of leisure, he's maddeningly purposeful. He first picked up a golf club four years ago, when Colbert volunteered to give him a lesson at the Bighorn Club in Palm Desert, Calif. Snyder beat balls in the sunshine for five hours until his hands bled. This fanaticism isn't new. When Snyder was 28, fresh from a year as a graduate assistant to John McKay at USC, he was hired to coach at Indio (Calif.) High, and he tried to have himself hypnotized so that he might compress six hours' sleep into an hour's trance. "The hypnotist just told me, 'That's not the way it works,' " Snyder says. At Iowa, where Snyder coached under Hayden Fry from 1979 to '88, his dissection of passing plays would reduce his fellow coaches to snickers. "Bill would've described a play for about two minutes, and he wouldn't even have reached the point where the quarterback releases the ball," says Wisconsin coach Barry Alvarez, who was the linebackers coach on that Iowa staff. Snyder has worn the same style of coaching shoes for two decades. When Nike stopped making the model in the 1980s, he hoarded as many pairs as he could find, and now on the sideline he looks like a character from That '70s Show. All coaches script their game days, and most script their practices. Snyder also scripts his staff meetings and insists that his assistants show him scripts for their position meetings. Kansas State players are required to wipe their feet before entering the athletic complex, they're not allowed to wear earrings, and their facial hair must be neatly trimmed. If a team meal is not served on time, Snyder marches into the kitchen to speed up the process. He refuses to discuss injuries with the press, and he tightly limits access to his players. The phrase control freak comes to mind, and Snyder doesn't fight it. "I probably do have that capacity," he says.

Wildcats coach Stan Parrish resigned after an 0-11 season in 1988, and athletic director Steve Miller was charged with finding a replacement. Sixteen candidates were interviewed. Jack Bicknell, then coaching Boston College, was offered the job and nearly took it, but at the last moment he pulled out. Jim Epps, then Kansas State's associate athletic director, suggested to Miller that they look at Iowa, which had rebuilt its program in the early '80s. "I was reasonably sure that we couldn't lure Hayden Fry to Manhattan," says Epps, "so I asked Steve, 'What about the coordinators?' " Epps grabbed an Iowa media guide and found that Snyder was the Hawkeyes' offensive coordinator. Epps called Snyder, who agreed to listen. Snyder knew all about rebuilding. Before Fry's arrival in 1979, Iowa hadn't had a winning season in 18 years, but since then it had averaged nearly eight wins per season and had played in three Rose Bowls. Snyder also knew offense. His passing game had given fits to Neanderthal Big Ten defenses. When Miller called Bo Schembechler of Michigan to ask about Snyder, Schembechler said, "Hire him, get him the f--- out of this conference."

Snyder arrived with a plan, and he stuck to it. "He was so damn focused," says Miller, now director of global sports marketing for Nike. "He was an AD's dream, because he worked so hard, and an AD's nightmare, because he wanted things. That first year, every time Bill came into the building, Jim Epps and I would just about hide under our desks, thinking, Oh, jeez, what does he want now?" He wanted his assistant coaches' salaries almost doubled, to be competitive with those in the top Big Eight schools. He wanted better facilities and a bigger recruiting budget. "All of this was difficult, because we were not only broke,we were in debt," says Epps. When there was no money to begin renovating the football complex, Snyder offered to write a $100,000 personal check. Instead, Kansas rancher Jack Vanier came up with the funds for the complex named in his honor. Then Dave Wagner of Dodge City, Kans., a $25-a-year contributor to the Wildcats, won $37 million in a 1991 national lottery drawing and donated $1 million to buy Kansas State new artificial turf. (Hence, Wagner Field.) Since Snyder's arrival the university has pumped $15 million -- modest by some standards -- into football facilities, and every penny has been paid by private donations. "I never wanted a Taj Mahal," says Snyder. He doesn't have one, but he no longer has a dump. The Wildcats won seven games in Snyder's third year, 1991. Snyder visited his friend Colbert in Las Vegas after that season, and Colbert told him to leave as soon as the right offer arrived. "I said, 'Coach, you've done a heck of a job, but when the big boys come calling, you ought to leave, because it's not going to get better at Kansas State,' " Colbert says. Two years later the Wildcats went 9-2-1, crushing Wyoming in the Copper Bowl. While walking to the team bus before that game, Snyder saw Colbert in the crowd, walked over and told him, "And you said it couldn't be done." Five years later Snyder oversees one of the most efficient programs in the country. Kansas State has won at least nine games for five consecutive seasons, and its current 16-game winning streak is second only to UCLA's 17. The Wildcats have milked junior colleges for good players, including quarterback Michael Bishop. But the principal reason for Kansas State's rise has been Snyder's relentlessness on the practice field. The Wildcats practice longer than almost any other team in the country. "Oh, my god," says Philadelphia Eagles offensive tackle Barrett Brooks, who played for Snyder from 1991 to '94. "Three hours. Three and a half hours. Every day. He'd kill us." That's how Kansas State has won with modest talent. Only one of Snyder's recruiting classes has been ranked in the top 20 by any service. Meanwhile, under Snyder the Wildcats program has engendered only one scandal: Last spring coveted junior college running back Frank Murphy received $3,000 from Wildcats supporters, which Kansas State reported to the NCAA and which resulted in Murphy's suspension for four games. By all appearances Snyder's tenure could serve as a model for reconstruction. "I've worked for Rich Brooks, John Cooper, Terry Donahue and Mike White, and this guy is absolutely the best there is," says Wildcats offensive coordinator Ron Hudson. "I've never worked harder, but you could put Bill Snyder anywhere -- any school, the NFL, anywhere -- and he would win."

Bill and his first wife, Judy, were married in 1964, while Bill was coaching at Indio High. They had three children: Sean and daughters Shannon and Meredith. Bill took the family with him to Austin College in Sherman, Texas, in 1974 and to North Texas State in 1976. By the time Bill arrived at Iowa in the winter of '79, he was divorced. "I was simply a bad husband, that's all," he says. "I was a faithful husband, but a bad one. You could certainly say that football was a part of it." He worked as hard then as he does now. "We never saw him," says Sean. In the summers following the divorce, the children would visit their dad in Iowa City and often run loose in the football complex while their father worked. As long as there is a team to coach, Bill will never throttle back his office hours. Yet he feels he is trying to be a better father and husband. He recruited Sean to Iowa and encouraged his transfer to Kansas State, where he became an All-America punter and now works as the Wildcats' assistant athletic director for football operations. "It's been wonderful just to get to see him every day," says Bill. In 1984 Bill married Sharon Payne, whose 21-year-old son, Ross Snyder, is a reserve running back for Kansas State. Bill and Sharon have a 12-year-old daughter, Whitney, whom Bill calls on those nights when he knows he will be returning home after she is asleep. He calls Shannon and Meredith every day and recently bought 42 acres of Texas land to be divided among his first three children. "He seems a lot more relaxed than he was 10 years ago," says Shannon. "Now I can go visit him and get him to go out to dinner." The most arresting moment in Bill's life as a father occurred on Feb. 14, 1992, when Meredith, then a senior in high school, was critically injured in a one-car accident near Judy's house in Greenville, Texas. Riding in the front seat between classmates, Meredith was thrown from the car, which flipped over seven times. When, after a seven-hour drive, Bill arrived at the Dallas hospital where Meredith had been taken, she was paralyzed from the neck down and breathing with the aid of a ventilator. Bill jumped into her life as never before, seeking out the best hospitals and rehabilitation centers, consoling Meredith when she needed it, pushing her like a football coach when she needed that. Within 2 1/2 months she was breathing on her own, and within six months she was walking with the aid of crutches or a cane. Meredith, now 24 and a junior at Texas A&M-Commerce, can drive a car without special instruments. She will be married in May. "Bill has really come through for Meredith," says Judy. "It's made up for all those years he wasn't there." "I can't tell you how much his encouragement has meant to me," says Meredith. "He has so much discipline, and he's instilled some of that in me."

There is another frame, on a facing wall. In it is an animation cell of a scene from Pinocchio. It's Snyder's favorite movie. He has bought dozens of copies of the videotape and sent them to his children and to friends and acquaintances who have kids. Geppetto, Pinocchio's creator in the film, captured Snyder's heart. "This guy had a tremendous passion for children," says Snyder. "Then he goes through disappointment, yet he has the compassion to stay with it." It is surely how Snyder sees himself, in life and in football. As Geppetto, the builder with a soul. HE'S HOME now. The suit jacket is laid neatly across the cooking island in the kitchen of his house in an upscale development three minutes from the stadium. In six hours he will be back in the office, chasing perfection again. Snyder is at the top of his profession and in the race for a national title. Yet, like any perfectionist, he despises finite goaIs. "If we're fortunate enough to win a national championship, I don't believe it would be a culminating experience," he says. "There's no finality in any of this for me, other than death." Is he happy? "I'm not unhappy," he says.

Soon the only sound in the kitchen is the rhythmic clacking of dress shoes on the hardwood floor, followed by the opening of a refrigerator door and the whisper of cool air flowing into the room.

|

Snyder's modest office above the north end zone of the stadium has become a mecca for the desperate. University presidents, business leaders, athletic directors and other football coaches seek Snyder's advice on how to set the first stones of rebuilding. "They expect me to reach into my top drawer and pull out a sheet of paper with a blueprint," says Snyder. "I'm flattered, but there's no piece of paper. We just got a little bit better every year for 10 years until . . . here we are." He went to work every day, just like his mother. Well, not quite like his mother. Not quite like anybody else.

Snyder's modest office above the north end zone of the stadium has become a mecca for the desperate. University presidents, business leaders, athletic directors and other football coaches seek Snyder's advice on how to set the first stones of rebuilding. "They expect me to reach into my top drawer and pull out a sheet of paper with a blueprint," says Snyder. "I'm flattered, but there's no piece of paper. We just got a little bit better every year for 10 years until . . . here we are." He went to work every day, just like his mother. Well, not quite like his mother. Not quite like anybody else.

OF COURSE, a man would need lots of control, not to mention lots of time, to right Kansas State football. Snyder inherited a 27-game winless streak when he was hired coach the Wildcats in November 1988. In the previous four seasons K-State had won three of 44 games. In fact, since the end of World War II, Kansas State had had only four winning seasons and played in one bowl game. "The teams I played on were rotten," says Dana Dimel, a Wildcat in '85 and '86 who assisted Snyder for eight years and is now the coach at Wyoming. When historian Jon Wefald became Kansas State's 12th president, in 1986, the university's enrollment and academic profile were slipping. Wefald improved both swiftly. Freshman enrollment grew by 1,300 students in his second year on the job, and K-State has since blossomed, ranking second in Rhodes scholarships and first in both Truman and Goldwater grants among the nation's 500 four-year public universities. Yet folks outside of Manhattan were slow to notice improvements, because so much negative attention was focused on the terrible Wildcats football team. "Face it, sports are the window through which the university is viewed," says Wefald. In 1986 average home attendance at K-State games was hovering around 20,000, and there were fewer than 7,000 season-ticket holders. Before the 1988 season Kansas State was so desperate for football revenue that it agreed to play its next five games against Oklahoma in Norman, because the road money there was better than the home money in Manhattan. The Wildcats' difficulties reached critical mass when Wefald's conversations with other Big Eight presidents led him to believe that they might expel K-State from the conference.

OF COURSE, a man would need lots of control, not to mention lots of time, to right Kansas State football. Snyder inherited a 27-game winless streak when he was hired coach the Wildcats in November 1988. In the previous four seasons K-State had won three of 44 games. In fact, since the end of World War II, Kansas State had had only four winning seasons and played in one bowl game. "The teams I played on were rotten," says Dana Dimel, a Wildcat in '85 and '86 who assisted Snyder for eight years and is now the coach at Wyoming. When historian Jon Wefald became Kansas State's 12th president, in 1986, the university's enrollment and academic profile were slipping. Wefald improved both swiftly. Freshman enrollment grew by 1,300 students in his second year on the job, and K-State has since blossomed, ranking second in Rhodes scholarships and first in both Truman and Goldwater grants among the nation's 500 four-year public universities. Yet folks outside of Manhattan were slow to notice improvements, because so much negative attention was focused on the terrible Wildcats football team. "Face it, sports are the window through which the university is viewed," says Wefald. In 1986 average home attendance at K-State games was hovering around 20,000, and there were fewer than 7,000 season-ticket holders. Before the 1988 season Kansas State was so desperate for football revenue that it agreed to play its next five games against Oklahoma in Norman, because the road money there was better than the home money in Manhattan. The Wildcats' difficulties reached critical mass when Wefald's conversations with other Big Eight presidents led him to believe that they might expel K-State from the conference.

Snyder, then 49, was comfortable in Iowa City. Friends warned him that Kansas State was a professional black hole. Indeed, none of the four head coaches who immediately preceded Snyder, dating back to 1967, ever became a college head coach again. Still, Snyder took the job. He took it by the throat and hasn't let go.

Snyder, then 49, was comfortable in Iowa City. Friends warned him that Kansas State was a professional black hole. Indeed, none of the four head coaches who immediately preceded Snyder, dating back to 1967, ever became a college head coach again. Still, Snyder took the job. He took it by the throat and hasn't let go.

COACHING HAS cost Snyder not just food, sleep and hobbies but also his first marriage and a role in the rearing of his first three children. This has been the central contradiction in his life. "My priorities have always been family, faith and football, in that order," he says, and yet football has consumed the vast majority of his time.

COACHING HAS cost Snyder not just food, sleep and hobbies but also his first marriage and a role in the rearing of his first three children. This has been the central contradiction in his life. "My priorities have always been family, faith and football, in that order," he says, and yet football has consumed the vast majority of his time.

Bill sat in his office during a recent foodless lunch hour. There is a framed picture of Meredith on the corner of his desk taken during a ski trip at Big Bear (Calif.), almost two years after her accident. "She made 12 runs that day and didn't fall once," he says. His eyes water as he looks long at the photo and says, "She's such a strong-willed girl."

Bill sat in his office during a recent foodless lunch hour. There is a framed picture of Meredith on the corner of his desk taken during a ski trip at Big Bear (Calif.), almost two years after her accident. "She made 12 runs that day and didn't fall once," he says. His eyes water as he looks long at the photo and says, "She's such a strong-willed girl."