|

BY TIM LAYDEN

© Sports Illustrated

THE LINE began just outside the Kansas State trophy room, where Wildcats seniors and their parents had gathered at a reception in weary celebration of a historic afternoon. The line stretched down a long corridor, through the lobby of the football complex and out onto a floodlit parking lot. Towheaded children with hair streaked in purple and senior citizens clutching souvenir Wildcat Growl Towels thrust slips of paper, trading cards, T-shirts and miniature footballs at Kansas State quarterback Michael Bishop, each trying to take home an autograph and a memory. In the sea of bodies surrounding Bishop were his parents, Artis and Ethel, and a cluster of other relatives and friends from his hometown of Willis, Texas, about 50 miles north of Houston. Also in the pack was Bishop's girlfriend, Kansas State junior Marilou Mewborn, holding a clear plastic plate of crackers and cocktail franks, ostensibly Bishop's dinner. Bishop, who was trying to make his way out of the reception, shuffled and signed, shuffled and signed. "I don't know why I'm holding on to this food," said Mewborn. "There's no way he's ever going to have time to eat it."

The mere prospect of the Wildcats' first win over the Cornhuskers in 30 years had prompted the sale of T-shirts emblazoned JUDGMENT DAY FOR THE CHILDREN OF THE CORN starting more than a month before the game, and the win touched off a riotous celebration that brought down the north goalpost in KSU Stadium and spilled into the bars of Aggieville in Manhattan. "All of us have waited a long, long time for this," said Dirk Ochs, who played defensive end for Kansas State from 1992 to '95 and whose brother, Wildcats senior linebacker Travis, made a critical sack of Nebraska quarterback Eric Crouch in the final minutes. In victory there was a delicious irony. Kansas State's program is built on a foundation of discipline and detail laid by relentless coach Bill Snyder, who was hired before the 1989 season. Woe to the player who so much as enters the locker room unkempt, for no indiscretion escapes the eye of the 59-year-old Snyder. Mistakes on the field are the least tolerable. Chad May, a Wildcats quarterback in 1993 and '94, recalls that Snyder could find a flaw in a seemingly perfect throw to a receiver wearing number 88 by pointing out that the pass was shaded slightly more to one eight than the other. This year, however, has seen the birth of the Michael Bishop Exception.

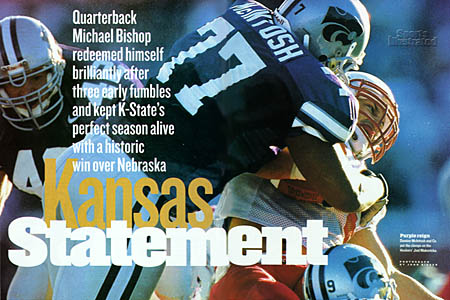

On Saturday afternoon Bishop nearly killed Kansas State's season by losing three fumbles in the first half (one on second-and-goal from the Cornhuskers' one with the scored tied at 7-7) and throwing an interception in the second. But Snyder's tolerance was rewarded as Bishop buried those errors in an avalanche of brilliance. Overall, he completed 19 of 33 passes for 306 yards and two touchdowns to senior wideout Darnell McDonald, and rushed 25 times for 140 yards and two more scores. Given ample reason to sulk, he instead played more effectively and with greater passion. For every slip, there was a play of unpredictable poetry. "No surprise," said Bishop's father after the game. "He did that kind of thing in grade school and he did it in high school. It just seems like he gets mad and plays better after he messes up." Still, Bishop at the controls of K-State's offense was like Andy Warhol running IBM.

More than an hour after Saturday's victory, Bishop fell into a soft chair in Snyder's office, letting out a protracted groan. "Just a little sore is all," he said. "I was getting hit on every play, whether it was a pitch or a pass or a run. I don't know if they were trying to take me out of the game or intimidate me, but they were hitting me." The early fumbles made him angry, but his game has no rearview mirror. "I couldn't wait to get back on the field after every one of them," he said. Not only did he play with more verve after miscues, but he also pestered Snyder and offensive coordinator Ron Hudson to adjust pass routes to take advantage of the huge cushion Nebraska defensive backs were giving McDonald, who caught 12 passes for 183 yards. "Michael has never done that before, and the things he pointed out were right," said Hudson. Bishop had seen similar cushions in tape study of the Huskers, and "once we got out there, they were just going into their backpedaling as soon as we snapped the ball," Bishop said. It should come as no shock that Bishop is not easily discouraged, either by his own mistakes or by the sustained pounding of a good defense. His road to Saturday's monumental victory was long and, at times, unpromising. As a senior at Willis High, he was dropped from recruiting lists when it became apparent he wouldn't meet the NCAA's core-course requirement for athletic eligibility. He played at Blinn College in Brenham, Texas, in 1995 and '96 and took the Buccaneers to consecutive national junior college championships, which helped atone for his failure to win a state high school title, a disappointment that still nags at him. "Texas high school football is big," Bishop says, "and I never got us to the big game." In Bishop's second year at Blinn, Baylor and Texas recruited him as a quarterback, and Texas A&M went after him as a wide receiver. Kansas State also entered the picture. The Texas schools were eliminated for various reasons: Texas already had James Brown at quarterback, Baylor had uncertainty at head coach, and Bishop wasn't going to play wide receiver anywhere. (Bishop also didn't pass an exam required by Texas junior colleges to obtain an associate's degree.) In December '96 he signed a letter of intent with Kansas State and transferred his Blinn credits to Independence (Kans.) Community College. Kansas does not require passage of an exit exam, but Bishop still needed an associate's degree to become eligible for football, and he got it in the spring of 1997. Bishop arrived in Manhattan almost two months before the start of camp for the '97 season and soon established himself as the best quarterback on campus. "I knew I could step in and make plays," he says. Bishop has started every game since. "The thing that has most often been overlooked about Michael is that he's only been in the program for a little more than a year," says Snyder. "We run a complex offense. It's amazing that he's learned as much as he has." It is equally remarkable that Snyder has been so tolerant of Bishop's miscues. "He makes mistakes and we have . . . conversations," says Snyder. "He doesn't get down on me, he corrects me," says Bishop. Sometimes he does more than that. Twice in Bishop's career, Snyder has prohibited him from talking to the media. The first was during a four-week period last season after Bishop publicly accused his teammates of quitting in a 56-26 loss at Nebraska, his only defeat since high school. ("He believes they did quit," says his father.) The second came this year, after Bishop told reporters that junior college transfer running back Frank Murphy had predicted that he -- Murphy -- would go 80 yards for a touchdown on his first carry in an upcoming game against Colorado. Snyder felt Bishop was setting up Murphy for abuse by Buffaloes defenders and silenced him again. "Michael sometimes says controversial things," says Snyder. The second ban, with occasional exceptions, is ongoing. Bishop spoke only to SI after Saturday's game. Despite these muzzlings, Snyder has an affection for Bishop, who has forced the coach to change his view of perfection, if not of interviews. "We live with Michael's mistakes because if we're not careful, we could temper a great talent," says Snyder. "Michael is a great all-around football player. That's what that trophy is supposed to be for, isn't it?"

The trophy in question would be the Heisman. Bishop was seldom mentioned as a strong candidate early in the season, and he still lacks the polish of Texas's Ricky Williams. Yet he makes plays, with his arm and his running ability, as few quarterbacks in the country do, and on Saturday he was the force that allowed a program to prove itself worthy of a No. 1 ranking.

Through the dying minutes, as Nebraska's final two drives failed and as Kansas State linebacker Jeff Kelly scooped up a fumble and ran 23 yards for a crowning touchdown, Bishop ranted up and down the sideline, waving, exhorting the crowd and in general expunging the foul taste of last year's loss in Lincoln. "When I got elected a captain this year," Bishop said, "I wanted to make sure the whole team was on the same page for Nebraska. I knew it was going to be a different game this time." Amid the growing delirium that followed Kelly's clinching score, as grown fans wept in celebration and students prepared to rush the field, the coach and the quarterback found each other on the sideline. Snyder first faced Bishop and placed one hand on each of his quarterback's shoulders as the two had an animated conversation, but one without humor. "I'm proud of the way you played today," Snyder told Bishop. "But we're going to go and look at the tape of that first half, and we're going to keep making you a better player."

Bishop nodded swiftly. Slowly the game faces dissolved into smiles and the coach's bloodless grab became an emotional hug.

|

Bishop is public property these days. He is the prized possession of Wildcats Nation, that giddy throng that has hitched itself to Kansas State during its remarkable rise from the dregs of college football to this year's 10-0 record and contention for the national championship. Despite the Wildcats' 40-30 victory over Nebraska last Saturday and Tennessee's narrow win over Arkansas (page 152), Kansas State remained No. 2 in the AP poll and third in the Bowl Championship Series standings, which will determine who plays for the national title in the Fiesta Bowl. The Wildcats did take sole possession of the top spot in the coaches' poll after Tennessee dropped a spot.

Bishop is public property these days. He is the prized possession of Wildcats Nation, that giddy throng that has hitched itself to Kansas State during its remarkable rise from the dregs of college football to this year's 10-0 record and contention for the national championship. Despite the Wildcats' 40-30 victory over Nebraska last Saturday and Tennessee's narrow win over Arkansas (page 152), Kansas State remained No. 2 in the AP poll and third in the Bowl Championship Series standings, which will determine who plays for the national title in the Fiesta Bowl. The Wildcats did take sole possession of the top spot in the coaches' poll after Tennessee dropped a spot.

Not that Kansas State has a wealth of other options. Faced with twice-beaten and struggling Nebraska's best effort since September, the Wildcats' offense was All Bishop, All the Time. Of their 76 offensive plays, Bishop ran or passed on 58 (76%), and on three others he made option pitches before being drilled to the artificial turf.

Not that Kansas State has a wealth of other options. Faced with twice-beaten and struggling Nebraska's best effort since September, the Wildcats' offense was All Bishop, All the Time. Of their 76 offensive plays, Bishop ran or passed on 58 (76%), and on three others he made option pitches before being drilled to the artificial turf.

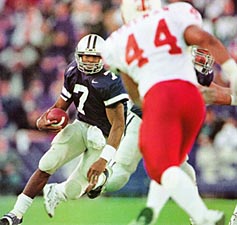

Kansas State, which came into the game ranked first in the country in scoring defense (7.7 points per game) and second in total defense (219.7 yards per game), gave up 351 yards to Nebraska. Offensive creativity was essential for K-State, and Bishop delivered. Two examples: In the second quarter, on second-and-11 from his own 19, Bishop went 50 yards on a scramble, thanks in part to a scalding midfield fake that left Huskers safety Mike Brown squeezing air. On the game-winning touchdown pass, with 5:25 to go, Bishop scooped a poor shotgun snap off the rug, sprinted hard to his right and threw a tight spiral across his body to McDonald, who was alone in the back of the end zone.

Kansas State, which came into the game ranked first in the country in scoring defense (7.7 points per game) and second in total defense (219.7 yards per game), gave up 351 yards to Nebraska. Offensive creativity was essential for K-State, and Bishop delivered. Two examples: In the second quarter, on second-and-11 from his own 19, Bishop went 50 yards on a scramble, thanks in part to a scalding midfield fake that left Huskers safety Mike Brown squeezing air. On the game-winning touchdown pass, with 5:25 to go, Bishop scooped a poor shotgun snap off the rug, sprinted hard to his right and threw a tight spiral across his body to McDonald, who was alone in the back of the end zone.